European Semester and Social Europe

Article

Jiri Sironen

Chair, Finnish Anti-Poverty Network EAPN-Fin

Online publication Future of Europe

© SOSTE Finnish Federation for Social Affairs and Health, February 2019

During the past decade, the European Union has increasingly developed its economic governance. The key procedure is an annual process called the European Semester. Born as a response to the European economic and sovereign debt crises, its main objective is preventing economic problems. During the Semester, the strategic targets of the Europe 2020 strategy are also monitored, and it is the main method of implementing the fresh Pillar of European Social Rights. By enhancing the social side of the Semester, it could be possible to steer the economic policy toward the support of wellbeing.

What is the European Semester?

In 2011, the European Union introduced the European Semester, to monitor and coordinate the economic policies of the member states. The Europe 2020 strategy, which is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs, is also coordinated through the Semester to increase education and employment, to promote research, to prevent climate change and to combat poverty.

During the European Semester, the Union observes the economic and social circumstances in the member states, and the measures taken to achieve the targets of the Europe 2020 strategy. The Union also undertakes an analysis of the economic and structural reforms of the member states and gives them recommendations.

The legal basis of the European Semester is defined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, TFEU, according to which economic policy and promotion of employment shall be considered uniform, co-ordinated matters.

Coordination is defined in more detail in the integrated guidelines, and the most important of these are the Employment Guidelines.

The Semester is also based on the Stability and Growth Pact – it sets a 3 per cent limit on public deficit and a 60 per cent limit on public debt in relation to GDP. In 2011, this set of rules was strengthened by the Six Pack legislation, and in 2012, by the Fiscal Compact agreement.

The Stability and Growth Pact sets a 3 per cent limit on public deficit and a 60 per cent limit on public debt in relation to GDP.

The European Semester is also a key implementing instrument of the European Pillar of Social Rights introduced in 2017.

How does the Semester work?

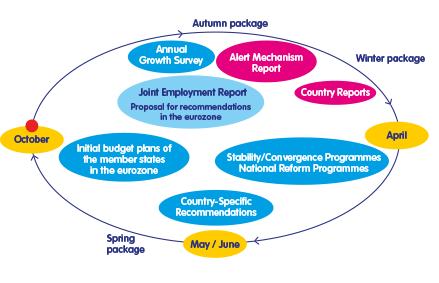

The main components and the timeline of the European Semester is described in the following:

The Semester kicks off in November with the autumn package launched by the Commission. This includes the Annual Growth Survey (AGS), and a Joint Employment Report (JER). In the Growth Survey, the Commission analyses the state of the Union economy and sets out general economic priorities for the following year.

In February-March, the Commission publishes the winter package, the main component of which are the Country Reports of each EU country. Based on these reports, the progress made by each country in economic, employment and social issues is assessed. The Country Report is a roughly 60-page view of the Commission of the economic and social development, challenges and prospects in each country.

The Country Report is a roughly 60-page view of the Commission of the economic and social development, challenges and prospects in each country.

In March, the European Council defines the main challenges in economic policy and political guidelines, which the member states shall consider when they publish their National Reform Programs (NRPs) in April. In them, they report their activities and plans to comply with the recommendations received by the Union and to implement the Europe 2020 strategy. The Ministry of Finance is responsible for drafting the Reform Programme in Finland. In April, the Stability Programme of each member state is also published. The General Government Fiscal Plan published in Finland each year contains a stability programme.

In May, the Commission publishes the spring package, its Country-Specific Recommendations (CSR). They contain a few pages of introduction summarising the analysis of the country reports and three summed up policy recommendations. The member states discuss the recommendations and approve them in the European Council in the summer. The member states are advised to take note of the recommendations when they draw up their budgets, and the euro countries present their budgetary plans to the Commission in September-October.

What does the Union recommend to Finland?

During the past eight Semesters, the Commission and the European Council have recommended to Finland e.g. maintaining the stability or strengthening and adjusting public finances; implementing the reform of the municipals and healthcare and social services; taking measures that prolong the working careers of the young and the elderly; promoting the employment of the long-term unemployed and immigrants; improving the incentives for accepting jobs; increasing competition in the retail trade and municipal services; diversifying business; approving the intended reform of the pension system; promoting a wage development complying with the development of productivity, while respecting the position of the labour market parties; and increased monitoring of the indebtedness of households.

Most of the recommendations have already been implemented in Finland – for example, regarding the stability of public finances the pension reform, promotion of competition and promoting the incentives for accepting jobs. Some of the recommendations may have remained partially unfinished, such as ensuring sufficient services for unemployed. The recommendation related to the reform of the regional government and social and healthcare services has evolved during the years: Firstly, a municipal reform increasing productivity had to be made, and the next step was to plan and carry out a successful reform of the social and healthcare services. Thirdly, an administrative reform increasing the cost-effectiveness of the social and healthcare services had to be secured, and in 2018 measures were to be taken to ensure that both cost-effectiveness and equal access to the services were guaranteed in it.

The recommendations include steps affecting the leeway of social policies as well as direct social policy measures.

What is known of impacts of the European Semester?

There exist different estimates about the impacts of the European Semester. It is generally estimated that 20-50 per cent of the recommendations have been carried out. According to a recent study (Efstathiou and Wolff 2018), Finland, Great Britain and Slovenia are among the countries that have implemented half the recommendations, whereas Luxemburg (23 per cent), Slovakia, Hungary and Germany (29 per cent) come at the bottom of the list.

It is generally estimated that 20-50 of the recommendations of the Semester have been carried out.

The assessment of the implementation of the recommendations is also complicated by their ambiguity. One recommendation may contain several parts, and with respect to social recommendations, there are multiple ways of carrying them out. The recommendations should be achieved during the next 12–18 months, but e.g. the Commission and the European Parliament assess their realisation even before that.

Social dimension of the European Semester

The European Semester may be considered the strongest political mechanism, through which the Union steers the social policies of the member states. Firstly, by determining the framework of public finances it significantly limits the leeway of social policies. Secondly, it affects the contents of social policies by issuing direct recommendations falling within its sphere.

By analysing the recommendations, it becomes clear that the Commission shows growing interest for social issues. In 2018, 63 per cent of the recommendations already contained individual sections relating to the field of social policies. This share has not previously been so large. Of the Finnish recommendations, two-thirds have touched upon social issues in some way (Clauwaert 2018).

The Commission has shown growing interest for social issues: in 2018, 63 per cent of the recommendations already contained individual portions relating to the field of social policies.

Interesting examples of the 2018 recommendations include e.g. the one given to Latvia about increasing the progression of taxation, ”Reduce taxation for low income earners by shifting it to other sources, particularly capital and property, and by improving tax compliance”; and the recommendation to Lithuania, ”Improve the design of the tax and benefit system to reduce poverty and income inequality”. But the recommendations also include examples of the promotion of employment by weakening unemployment benefits or employment relationship benefits, which would be likely to have impacts increasing poverty.

The increasing attention to social policy issues may also be explained by the fact that the Semester is – in addition to legislation and EU funds – the key instrument of implementation for European Pillar of Social Rights established in 2017.

The Pillar brought with it a Social Scoreboard containing 12 social indicators, which were added to the Semester and the country reports. However, no minimum or target values have been defined for the indicators. In the Social Scoreboard of the country reports, the performance of each country is colour-coded on a scale of ”critical situation” and ”best achievers” at the opposing ends of the spectrum. Even if such a scale can be used to identify critical situations requiring measures in different countries, the other end of the scale can be criticised for not focusing attention on the progress of the said county in achieving its targets, and the country may retain its place as one of the best achievers in relation to others, even if its circumstances would continue to grow worse.

Agreements and recommendations – criticism on the dominance of macroeconomics

The hard core of the Semester can be said to be comprised of monitoring the economic policies of the member states, where the toolbox even contains fines imposed on member states and non-approval of budgetary proposals. The social aspect of the Semester may often be reduced to the level of recommendations.

Macroeconomic issues dominate in the Semester in relation to other policy areas, as it relies on binding legislation. Because of the macroeconomic legislation, the stability of public finances and the debt sustainability of the member states outweigh employment and social goals.

Because of the macroeconomic legislation, the stability and debt sustainability of public finances outweigh employment and social goals.

Part of the Semester, the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure MIP Scoreboard contains thresholds that have been defined for the economic indicators which trigger further measures, such as a detailed examination or a procedure on excessive imbalance. Greece has remained outside the annual Semester until autumn 2018, as it has participated in the economic adaptation programme of the Union. The binding nature of social indicators, goals and recommendations is hence quite different from other forms of economic steering.

More social and more democratic Semester?

Whatever the opinion on the Semester, it is important to follow its advance and seek to influence it. The Semester is the leading political process of the Union and can affect the future of the member states and the Union. The Semester also has growing importance for the allocation of EU funds.

NGOs in the field of social affairs have presented several ideas for reinforcing and democratising the social side of the Semester. The Finnish Anti-Poverty Network EAPN-Fin has e.g. discussed an assessment of the social impacts of the Semester, which would facilitate preventing economic decisions with socially harmful impacts. The number of social indicators should be increased further and their impact in decision-making ensured, for example by introducing flexibilities to the macroeconomic rules and by specifying thresholds which would trigger an in-depth examination of the situation in a specific country. The rules of the Stability and Growth Pact should also be re-evaluated and social investments should be left outside the interpretation of economic rules.

The European Anti-Poverty Network EAPN finds that despite the European Pillar of Social Rights and promises to balance the Semester with social issues, the approach of the Union and the member states still emphasises macroeconomic discipline, and the realisation of social rights, let alone reduction of poverty, has not been prioritised. Within the Semester, it has not been possible to analyse the social impacts of changes in taxation and social security, flexibilities in the employment market, or privatisation. EAPN supports a more sustainable model of growth, where the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights and sustainable development would lead to a reorientation of economic policy to reduce inequality and to ensure wellbeing. EAPN hence proposes that the Stability and Growth Pact would be changed into the Stability and Wellbeing Pact.

Within the Semester, it has been impossible to analyse the social impacts of changes in taxation and social security, flexibilities in the employment market or privatisation.

The responsibility for carrying out the Semester is divided between the various organs of the Union – the Commission, the Parliament and the European Council composed of the prime ministers of the member states – and the governments of the member states. However, the implementation of the Semester should be carried out in cooperation with the parliaments, social partners represented by labour market organisations and the NGOs. (An explicit mention of NGO representatives was added to the employment policy guidelines only in 2018). There is very little open discussion about the Semester in Finland; it is mainly discussed in the Commission events. More channels should be available for the participation of the Parliament and the whole civil society, and such channels could include the public hearings and open debates of the Grand Committee. The participation of the NGOs in the Semester has so far varied per country, and in Finland it has been largely up to the Commission. The NGOs have so far had no opportunity to discuss the Finnish national reform programme prior to its publication. The media could also study the Semester with more diligence and provide more comprehensive reports about it instead of merely publishing economic growth forecasts.

The cards of the present Commission and the European Parliament have been on the table for quite some time, and it is up to the new Commission and the European Parliament to develop the Union and European Semester in the future. Fortifying social Europe would be possible within the framework of the European Pillar of Social Rights or the next overall strategy, if there is enough political will.

References

- Efstathiou, Konstantinos and Wolff, Guntram B.: Is the European Semester effective and useful?, Policy Contribution Issue n˚09, June 2018, https://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/PC-09_2018_3.pdf

- Clauwaert Stefan: The country-specific recommendations (CSRs) in the social field, An overview and comparison, ETUI 2018

- Kattelus Mervi, Saari Juho ja Kari Matti: Uusi sosiaalinen Eurooppa, Euroopan unionin sosiaali- ja terveyspolitiikka, Eurooppatiedotus 2013, New Social Europe, the Social and Health Care Policy of the EU, Europe Information

- Make participation a driver for social rights, EAPN Assessment of the NRP´s 2018, www.eapn.eu More audacity to fight poverty and ensure social rights!, EAPN Assessment of the 2018 Country-Specific Recommendations 2018, www.eapn.eu

- Sabato, S., Ghailani, D., Peña-Casas, R., Spasova, S., Corti, F. and Vanhercke, B., Implementing the European Pillar of Social Rights, European Economic and Social Committee 2018

- Toolkit for EAPN members on engaging with the European Semester and the European Pillar of Social Rights, 2018, www.eapn.eu

This is an article of the online publication Future of Europe.

© SOSTE Finnish Federation for Social Affairs and Health, February 2019